How to survive in the next renaissance: Read History and Understand How the World Works

This is essay 1 for The Network State Writers Cohort #5: The last and the next renaissance, why old people likes history, natural philosophy

Renaissance: From the last one to the next

When we hear "renaissance," we think of Europe’s 15th-century revival—da Vinci, Michelangelo, and jaw-dropping masterpieces. But a renaissance is more than art; it’s a disruptive transformation of technology, society, and life itself.

Europe’s last scientific renaissance brought it from feudalism and strict religious dogma into an age of exploration and innovation. Two books shaped my understanding of this shift. “1492: The Year the World Began” by Felipe Fernández-Armesto explains how shipbuilding innovations fueled global expansion, think Columbus crossing the Atlantic. And from “Civilization: The West and the Rest” by Niall Ferguson, highlights how competition between neighbouring states supercharged innovation, driven by the criss crossing of intellects and scientist migration from religious or political persecution, whether across the liberal Prussian territories, Dutch lowlands, and the other central European kingdoms.

Consider Gutenberg’s printing press—few grasped its impact at first, but it reshaped the world. The internet and AI may be today’s equivalent. While experts argue AI has been around for decades, it’s now usable and cheap for the masses. Does that mean we’re entering a new renaissance? Ray Kurzweil thinks so, proclaiming The Singularity Is Near—or now, nearer.

Yet, for most people life remains oddly familiar. For work, we still grind nine-to-five, even if we spend hours Zoom calls. For entertainment, we still binge endless shows like the middle class Simpson families. Only now with a personal screen that fits in our pockets, rather than the fireplace type of large LCD screen.

It’s this tension, between revolutionary progress and routine, that makes me wonder: How do we prepare for a new renaissance? How can we survive and pass along our gene pool in the process?

To answer this 1 trillion dollar question, I’ve turned back to the basics, reading more history to see how the past reshaped current and future society.

It’s still unclear which geographic region is about to experience the revival of the renaissance: the self-proclaimed “golden age” in America, the surge in centralized AI and robotics across China, or the infinite frontier of the internet and new form of network state. But it feels to me that the ocean is boiling. And History suggests those who anticipate changes and stay open to surprises will likely to survive.

Why Old people Like History?

No matter where you’re from, you might notice that older people often talk about the past. Sometimes even glorifying it. My late grandfather, for example, was an avid collector of artifacts and spent his final years in his open-air study, reading endless historical books. Though mostly about his ancestral kinship. As a kid, I didn’t understand what’s fun about it. As a kid, I didn’t get it. But once I lived longer than the average medieval person (who rarely saw their 30s), I think I understand.

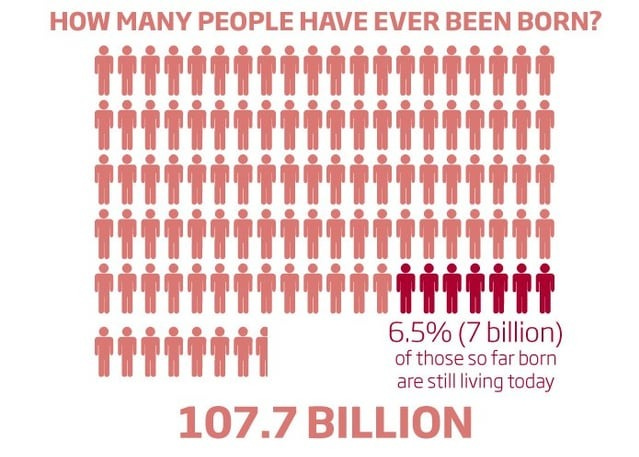

Morgan Housel put it best: "The dead outnumber the living 14 to 1, yet we ignore the accumulated experience of such a huge majority of mankind."

As a non-European immigrant who first came to study and is now starting a business in Germany, I’d be foolish not to learn from the deep history of this old continent. Books like “The French Revolution and What Went Wrong” by Stephen Clarke, showed me how society was divided into three groups—clergy, nobility, and civilian merchants,and how those roles shaped and controlled society. I’ve also learned about wild currency collapses when regimes printed too much money, like the assignats in revolutionary It all feels surprisingly familiar to our modern era, doesn’t it?

Another example from my lessons learned from history comes from Max Weber’s “The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism”, where he describes how Protestants in Germany and other parts of Europe, barred from government positions, worked hard to gain wealth and status through commerce. I’ve seen a similar pattern among the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia, who found prosperity in business because they are not allowed to join the political arenas. Weber also noted that some groups prioritized leisure over money—an early version of today’s work-life balance debate. And just as German factory workers once resisted new machines, many today resist AI tools that could make them more productive. Some things never change.

A recent binge watching of history I’ve picked up is from Dr. Roy Casagranda, a history professor from Austin who posts long engaging YouTube lectures on topics like “How Islam Saved Western Civilization” and other amazing historical stories. He emphasizes multiple times how events follow an action-reaction pattern. From the past to the present, combining facts and analogies.

History might not repeat itself exactly, but the parallels are striking. As David Deutsch, author of “The Beginning of Infinity”, points out, no one can predict the future growth of knowledge because no theory can perfectly predict its own successor.

If a new renaissance is coming, we may face the same mix of growth and turmoil seen in the past. People with contrarian views could be “canceled” or even jailed. Like Galileo Galilei, punished by the Catholic Church for introducing Heliocentrism (Which stated the sun is the center of the universe, not Earth as it was long believed). Or John Harrison, who invented the marine chronometer, revolutionized modern navigation but had to fight for recognition. Real progress often seems destructive at first, like a forest fire clearing deadwood or a rigorous Korean skincare routine peeling off old layers.

Adlerian psychology, as outlined in “The Courage to Be Disliked” (A hot book in X Tech circle at the end of 2024), argues we’re not just products of our past but can choose our future. Both psychologically and physically. You never step into the same river twice—both you and the river are always changing.

So yes, history can help us prepare for the next golden age of technological growth. But it’s not everything. Only after several years of reading history and philosophy, I’ve just realized that the answers also lie in understanding how the world actually works, what people used to call “natural philosophy”.

Natural philosophy: an intro to how the world works

Reading history, packed with warriors, drama, and philosophical wisdom, is a great source of entertainment for me. It let me escape the present time and experience the greatness of the past. But I’ve always felt something was missing: a coherent, factual, almost mathematical way to explain events and experiences. That led me to peek into physics.

Physics come from the Greek word for “nature”, and for centuries, it was called natural philosophy, covering everything from astronomy to medicine. It aimed to explain the world without resorting to the supernatural.

My first taste of physics was in high school. My dad forced me down the science route, even though I had a natural curiosity for history (Once I scored 100 on a history test). Back then, physics felt like random and torturing formulas to memorize for exams. Practical exercise such as building spaghetti bridges was fun, but it didn’t click for someone not heading to engineering school.

Only years later, after reading thinkers like Nassim Taleb and David Deutsch (thanks to Naval Ravikant’s recommendations), did I realize physics explains much of life in clear, factual terms. So I decided to give it another try.

I started with “The Handy Quantum Physics Answer Book”, a suggestion from my Dad who says it’s an easy starting book. Maybe for him, who spent years teaching engineering at the best University in Indonesia. For me, it was too much, I felt even more stupid.

Fortunately ChatGPT helped me find better basic books such as “For the Love of Physics” by Walter Lewin and “Existential Physics” by Sabine Hossenfelder. These authors have millions of YouTube views because they simplify without dumbing down, a sign they truly know their shit.

In this article, I won’t pretend I’ve mastered basic physics yet, so I won’t fake my insights. But I’m documenting my learning process on X (learning in public, as they call it). And will share more of my learning in the future.

Recently, I met an astrophysicist at a Berlin book club who once focused purely on physics but now sees the philosophical side, too. Funny—he came from science to philosophy, and I’m moving the other way. Yet we’re arriving at the same intersection. Just like Renaissance thinkers who mastered both the "hard" and "soft" sides of knowledge, guiding them through business, war, politics, and life itself.

Okay back to reading now. Thanks for being here, see you in the next article :)

If you enjoy reading this, check out my fellow Network State Writers @https://nsconnect.xyz/media